Pink Rain

With the recent stormy weather here I felt inspired to make some art. This manifested in a real time pink noise generator with accompanying torrential rain visual as depicted in the GIF below.

I implemented this using Rust and the Nannou crate which makes interfacing with audio devices and graphics very straight forward. In this article I’ll be briefly discussing the algorithm used to generate the ‘rain’ sound. The full source code for the project as well as the model can be found here.

What is Pink Noise?

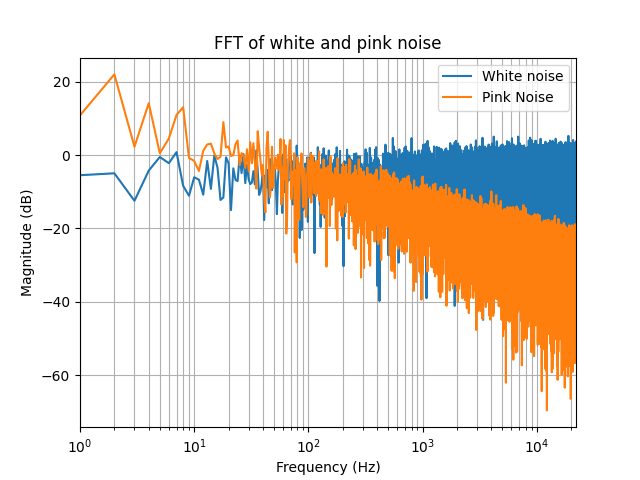

Pink noise is characterised by its 1/f frequency response (and is thus sometimes referred to in literature as ‘1/f noise’)1. Where white noise has a flat frequency response across all frequencies in the sampling range, Pink noise has a sloped frequency response at -10dB per decade1. The figure below shows the frequency responses for a white noise and pink noise signal respectively.

Pink noise is of particular interest to the scientific community due to its prevalence in various natural phenomena 2. With regards to the generation of pink noise, there has been a lot of discussion with how best to achieve this 1 3 4 5. Most of the techniques I’ve encountered are some variation of filtering a white noise signal with a “pinking” filter that has a frequency response of roughly -10dB per decade. There is also algorithmic methods of producing pink noise, one of which will be discussed in this article.

Voss McCartney Algorithm

The Voss-McCartney algorithm is one of the aforementioned techniques for generating pink noise. The original algorithm involves having multiple white noise generators that each update at different rates which are then summed every sample period 1 3. The average of all these white noise sources produces the next pink sample. McCartney suggested an improvement where only one of these white noise generators would update each sample. The next pink sample is then generated by subtracting the generator’s previous value and then adding its latest value 1. The GIF below shows a series of white noise generators that each update at different sample rates like in the algorithm.

As you can see, the topmost generator is updating every sample, the one below every 2nd sample and so on. Summing and normalising these generators produces samples with a pink frequency response.

Implementation

To begin with I needed a method of generating white noise. This was achieved (naively) with the following snippet of rust:

use rand::random;

...

let noise = (random::<f32>() * 2.0) - 1.0;This produces a random number in the range [-1.0, 1.0). I encapsulated this as a Noise class (shown below) which could be used to define any number of noise generators.

use rand::random;

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

pub struct Noise{

value:f32,

}

impl Noise{

pub fn new() -> Noise{

Noise{

value: 0.0,

}

}

pub fn update(&mut self){

self.value = (random::<f32>() * 2.0) - 1.0;

}

pub fn value(&self) -> f32{

self.value

}

}Next was to implement the actual Voss-McCartney algorithm which I did as a Pink class which is shown in the sample below. Upon instantiating, a number of variable rate noise generators are defined (noise) as well as generator that updates every sample (white). The counter, which is used to determine which generator to update, starts at 1. This is because to my understanding, the count_trailing_zeros instruction is undefined for a value of 0 (at least for GCC anyway)6. McCartney hints in his original discussion that this instruction can be applied to the counter to return an index for the given noise generator to update 1 3. Finally, the rollover is calculated to prevent a disjointed update sequence when the counter exceeds the limit of a u32. The rollover is calculated as 2^(generators - 1), which is the first time the final generator is updated. When the counter exceeds this rollover value, it is reset back to 1 and the cycle continues.

pub use crate::noise::Noise;

const GENERATORS: usize = 15;

pub struct Pink{

noise: [Noise; GENERATORS], // updated based on trailing zeros

white: Noise, // Updated every iteration

pink: f32, // Actual noise

counter: u32,

generators: u32,

rollover: u32,

}

impl Pink{

const GENERATORS: u32 = GENERATORS as u32;

pub fn new() -> Pink{

Pink{

noise:[Noise::new(); Self::GENERATORS as usize],

white: Noise::new(),

pink: 0.0,

counter: 1,

generators: Self::GENERATORS,

rollover: 2u32.pow(Self::GENERATORS - 1),

}

}

fn get_noise_index(&self) -> u32{

assert!(self.counter > 0);

assert!(self.counter <= self.rollover);

self.counter.trailing_zeros()

}

fn increment_counter(&mut self){

assert!(self.counter > 0);

assert!(self.counter <= self.rollover);

self.counter = self.counter & (self.rollover - 1);

self.counter = self.counter + 1;

}

pub fn update(&mut self) -> f32{

let index = self.get_noise_index() as usize;

assert!( index < self.generators as usize );

self.pink = self.pink - self.noise[index].value();

self.noise[index].update();

self.pink = self.pink + self.noise[index].value();

self.pink = self.pink - self.white.value();

self.white.update();

self.pink = self.pink + self.white.value();

self.increment_counter();

self.pink / (self.generators as f32 + 1.0)

}

}In order to use this class, the user simply needs to instantiate it using let mut pink = Pink::new(), and then call the update() function every sample period. Upon calling this function, the instance of the class first gets the index for the generator to update. The generator’s previous value is then subtracted from the cumulative total stored in pink. A new noise sample is then generated and added back. The same is repeated for the white noise source that updates every sample iteration 1 3. The counter is then updated and a normalised value is returned to the caller so that it can be passed to the output device.

The increment_counter function is worth some further discussion. Here the wraparound check is done prior to incrementing the value. This is done so that the counter always starts at 1 and always ends at rollover rather than 0 and rollover - 1.

Demonstration

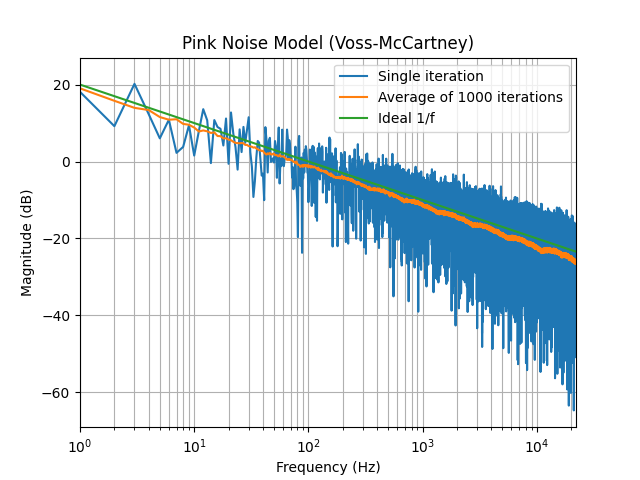

Prior to implementing the algorithm in Rust I modelled it in python so that I could check the frequency response. The image below shows the averaged frequency response of 1000 pink noise samples generated using the Voss-McCartney algorithm alongside the ideal -10dB/Decade line and a single run of the algorithm.

As you can see, the averaged response has roughly the same gradient as the ideal 1/f line (0.53 vs 0.5 respectively). There’s some noticeable ripple there, though that is insignificant to the human ear. If the pink noise was for instrumentation purposes I would probably try the ‘pinking’ filter approach to get a more accurate response. For the sound of torrential rain though this works nicely.